Gregory Robinson details the journey of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope for Gilleo Lectureship

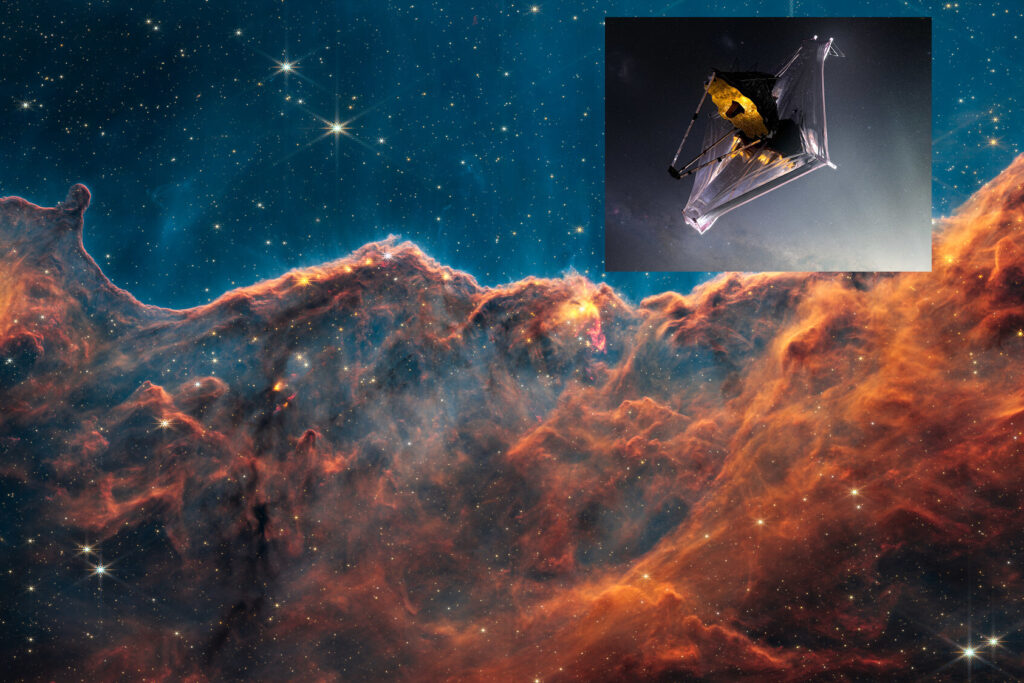

Launched a little more than a year ago, NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST or Webb) has delivered dazzling, never-before-seen views of the universe and revolutionized our ability to study distant galaxies, nebulae, and spectacular cosmic events. But while many consider the JWST to be one of NASA’s greatest achievements of the 21st century, the journey was anything but optimal.

As this year’s M. Alten Gilleo Distinguished Lectureship speaker, Dr. Gregory Robinson, a 33-year veteran of NASA, detailed the fraught history of the JWST and how he was tasked with righting a project that was years behind schedule and billions of dollars over-budget.

“A book I keep on my desk all the time is called Lion Taming,” Robinson said during the April 10th lecture in STAMPS auditorium. “There are times when you need to roar, and there are times when you need to tame. Leadership is about determining which one you need and when.”

The JWST is an orbiting infrared observatory that is 100 times more powerful than the Hubble Space Telescope with a primary mirror that is approximately 6.5 meters. It studies every phase in the history of our Universe, ranging from the first luminous glows after the Big Bang, to the formation of solar systems capable of supporting life on planets like Earth, to the evolution of our own Solar System. As the premier observatory of the next decade, the JWST serves thousands of astronomers worldwide.

“So why do we do these astrophysics missions?” Robinson said. “Of course, the big questions are: how do we fit into this vast universe? How did we get here? And: are we alone? And Webb is intended to help us better understand that.”

The JWST began as an idea in 1989 and construction began in 2004. One of the biggest challenges of the JWST was that multiple new technologies had to be developed for the project to even be possible.

“For most missions, there are one, two, maybe three new technologies,” Robinson said. “On Webb, there were ten plus new technologies that had never been designed, built, or flown before. It’s nuts.”

These new technologies include an ultra-lightweight beryllium primary mirror made of 18 separate segments that unfold and adjust to shape after launch. The biggest feature is a tennis court sized five-layer sunshield that attenuates heat from the Sun more than a million times. The telescope’s four instruments – cameras and spectrometers – have detectors that are able to record extremely faint signals. One instrument (NIRSpec) has programmable microshutters, which enables observation of up to 100 objects simultaneously. The JWST also has a cryocooler for cooling the mid-infrared detectors of another instrument (MIRI) to a very cold 7 K so they can work.

“The Webb telescope is one of the most exciting feats of engineering in optics in the past decade, with a dramatic and successful launch,” said Theodore Norris, the Gerard A. Mourou Professor of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, who serves as the Gilleo Lecture faculty host. “Many people from Optics to Astrophysics to Space Science to the general public have been very excited to follow the development, so we thought it would be a great idea for Greg to come tell the story.”

The Webb telescope is one of the most exciting feats of engineering in optics in the past decade, with a dramatic and successful launch.

Prof. Theodore Norris

For years, the JWST project was plagued by engineering failures and disorganization. Then, Hurricane Harvey hit the Gulf Coast, causing even more havoc for the JWST team based at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, TX.

“That made things quite challenging,” Robinson said. “Teams set up cots in the center and slept there. They were going out into the community to help people out. You won’t find many teams smarter than this one, but their resiliency is unparalleled. They just hung in there every step of the way.”

Seven months later, Robinson took over as head of the project, tasked with righting the ship, as it were. Despite even more challenges – the COVID-19 pandemic, included – Robinson managed to bring together 20,000 people across 29 countries and 14 U.S. states to not only turn the program around, but nearly double its efficiency.

“I took over a very smart, resilient team, but the culture needed some shifting,” Robinson said. “Everyone was doing the right jobs, and for the most part the right way. There were a few things just misaligned.”

Under Robinson’s leadership, the JWST successfully launched on December 25, 2021, from the European Space Agency (ESA) spaceport in French Guiana.

“Seeing that solar ray deploy was one of the best scenes I’ve seen in my life,” Robinson said. “The control room just went nuts.”

For his achievement, Time magazine listed Robinson as one of the 100 Most Influential People of 2022 and a Time100 Impact Award winner, which credited his leadership on the JWST as bringing us closer to understanding the universe. He was also named 2022 Federal Employee of the Year.

In addition to the lecture, Robinson met with several current students for a luncheon discussion. He shared his career journey, his path to leadership, and his perspectives on the role NASA/the government plays in advancing innovation in the country.

“My biggest takeaway from the conversation was the importance of mentors even in professional circles,” said Demba Komma, an ECE PhD student. “He went into management due to his mentors pushing him towards that area and pushing him to enroll in some training NASA offers for management.”

Robinson also gave advice to the students regarding their future careers.

“I am going to be working at JPL [NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory] this summer, and it was nice to see how genuinely excited he was for me to be working there,” said Angela Wang, a dual Master’s student in ECE and Aerospace Engineering. “It’s comforting in the sense that people seem to enjoy working for NASA and in part explains why so many of their employees stay for so long. I’ll be following his advice about being inquisitive and I hope to meet other inspiring people like him.”

Robinson previously served as Deputy Center Director at NASA’s Glenn Research Center in Cleveland, as well as NASA’s Deputy Chief Engineer from 2005-2013. He also served as the acting National Environmental Satellite, Data, and Information Service Deputy Assistant Administrator at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), where he led the acquisition and management of all NOAA satellite systems. Prior to Robinson’s reassignment to NASA Headquarters in 1999, he spent 11 years in various leadership positions at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

The JWST is an international collaboration between NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA), and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The NASA Goddard Space Flight Center managed the development effort. The main industrial partner is Northrop Grumman; the Space Telescope Science Institute operates the JWST after launch.

View photos from the lecture here.

About the M. Alten Gilleo Distinguished Lectureship

The M. Alten Gilleo Distinguished Lectureship in Optical Sciences and Optoelectronics brings the world’s top researchers in the field of optics and optoelectronics to Michigan. The Lectureship was established by Anita Gilleo (BS Lit ‘44) in honor of her brother, Mathias Alten Gilleo (BSE EE ‘44). Alten Gilleo made significant contributions to optics and solid state physics throughout his career, and worked in some of the most advanced research labs of his time.