New biodegradable hydrogel offers eco-friendly alternative to synthetics

A water-absorbing hydrogel made from bacteria provides a safer soil solution.

Enlarge

Enlarge

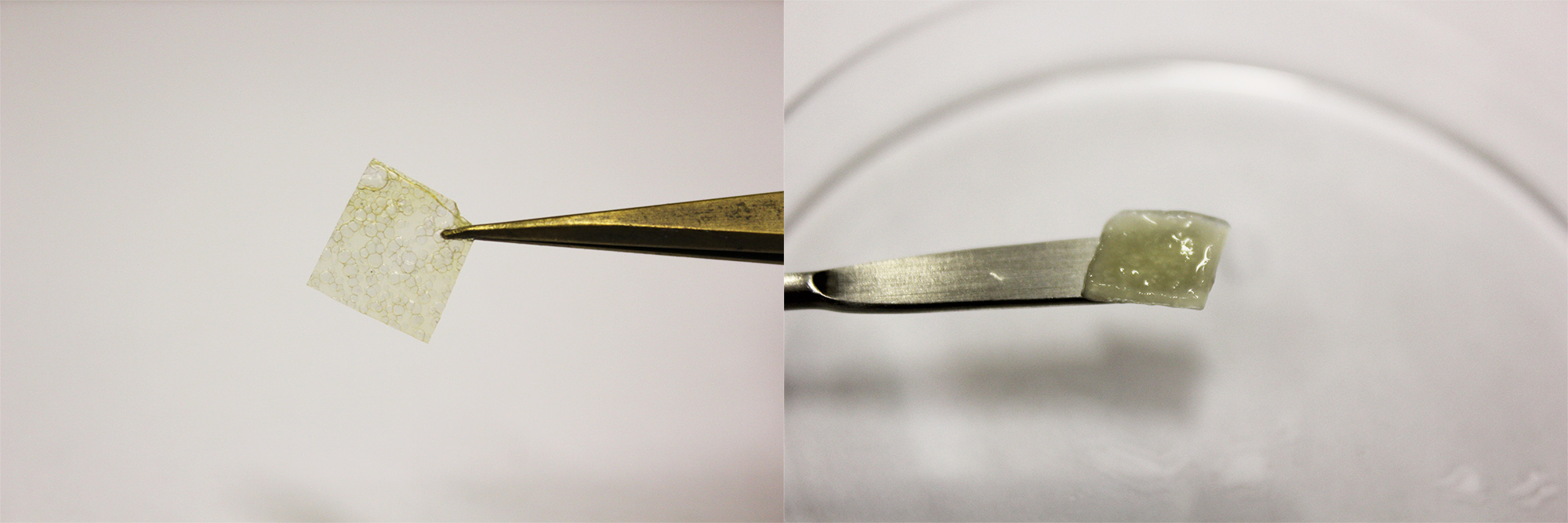

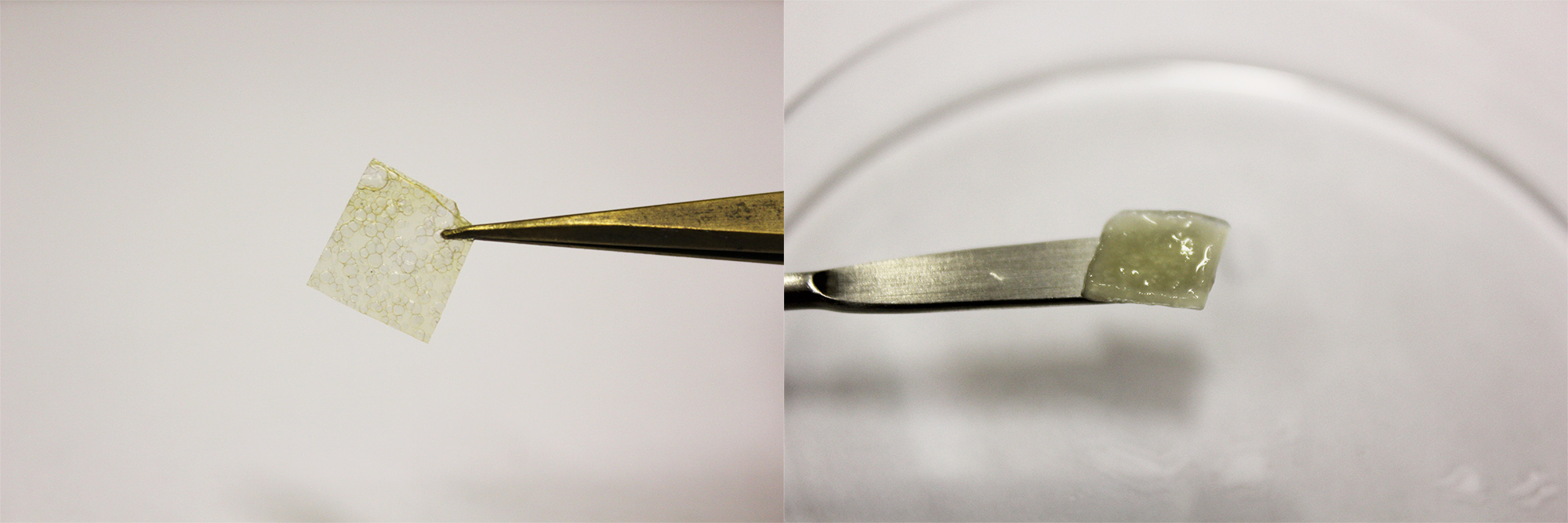

Researchers have developed a new hydrogel made from natural and biodegradable materials that allows for applications in agriculture and medicine without the potential risks of synthetic hydrogels.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Hydrogels are polymers, compounds of repeated smaller molecules called monomers, which have the ability to absorb large amounts of liquid. They can commonly be found in diapers to retain water and accompanying flower bouquets to keep plants hydrated. Typical hydrogels, however, are made from synthetic materials, like polyacrylamide, that do not decompose.

In an international collaboration, Jerzy Kanicki, professor of electrical and computer engineering at U-M, and Agnieszka Pawlicka, professor of chemistry at University of São Paulo and formerly visiting scholar at U-M, created a biodegradable hydrogel with gellan gum, which is produced by bacteria. Their paper is featured in the Journal of Applied Polymer Science.

A primary use of synthetic hydrogels is to help grow crops in dry areas. The hydrogels can swell with water during rains and release the moisture into the soil during dry times, both watering plants and helping to control erosion. Fertilizer is also added to hydrogels, allowing for a slower release of nutrients into the soil.

Enlarge

Enlarge

The effects of placing synthetic hydrogels in soil are debated, especially as the polymer degrades. Polyacrylamide hydrogels can physically break down into acrylamide, a known neurotoxin to humans. While acrylamide itself can biodegrade, Cathy Seybold, a soil scientist with the United States Department of Agriculture, notes, “the major source of acrylamide that is released into the environment is from the use of polyacrylamide products, so the FDA regulates the residual monomer content of polyacrylamide used in food contact products.”

Kanicki and Pawlicka’s biodegradable hydrogel, however, breaks down into sugars, carbon, and carbon dioxide.

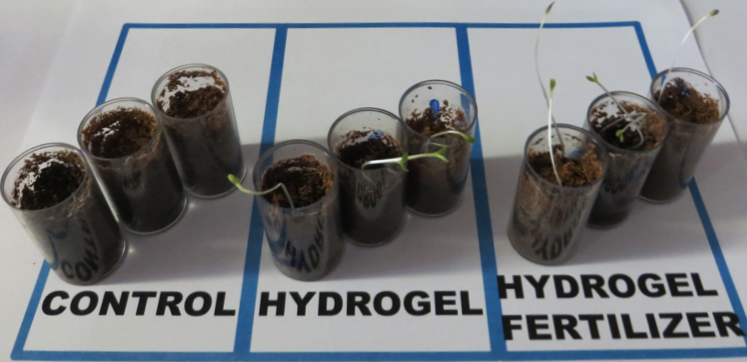

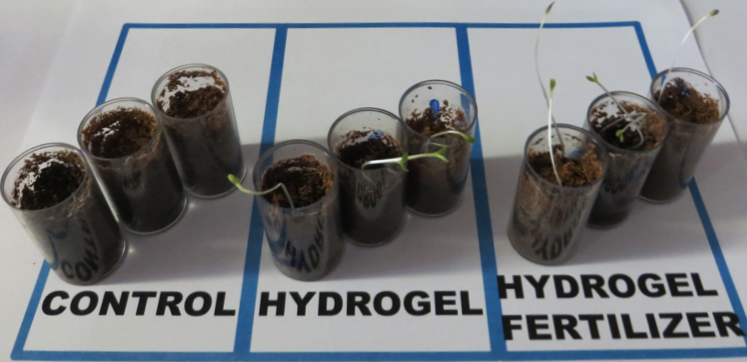

Kanicki and Pawlicka also experimented with adding fertilizer to their hydrogels. Just like synthetic hydrogels, the fertilized biodegradable hydrogel was placed in soil, and after watering, slowly diffused the fertilizer. This resulted in a noticeable difference in germination of sample lettuces seeds.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“We have the same advantages as synthetic hydrogels: it allows for an economic use of fertilizer and water,” says Pawlicka. “Except, our natural hydrogel biodegrades.”

“This was just the beginning, but the end idea is to combine this with an array of sensing devices,” says Kanicki. “You could adjust the hydrogel based on the location, the amount of precipitation, and how fast the plants are growing. It’s intelligent monitoring of agriculture.”

“You could adjust the hydrogel based on the location, the amount of precipitation, and how fast the plants are growing. It’s intelligent monitoring of agriculture.”

Jerzy Kanicki

Kanicki also dreams of utilizing the hydrogels in medicine. “We could use it to absorb and analyze the ions within sweat for signs of stress,” he says.

“This hydrogels’ molecules are human-body friendly, and much better than many others,” Pawlicka adds. “This makes it a great choice to deliver medication over time, like it delivers fertilizer to plants over time.”

Researchers include Rodrigo Sabadini, a post-doctorate researcher at the Instituto de Quimica de Sao Carlos, University of São Paulo (Brazil), and professor Maria Manuela Silva, University of Minho (Portugal). The team is seeking to commercialize the agricultural applications in Brazil.