Queen of the hurricanes: An engineer and feminist for the ages

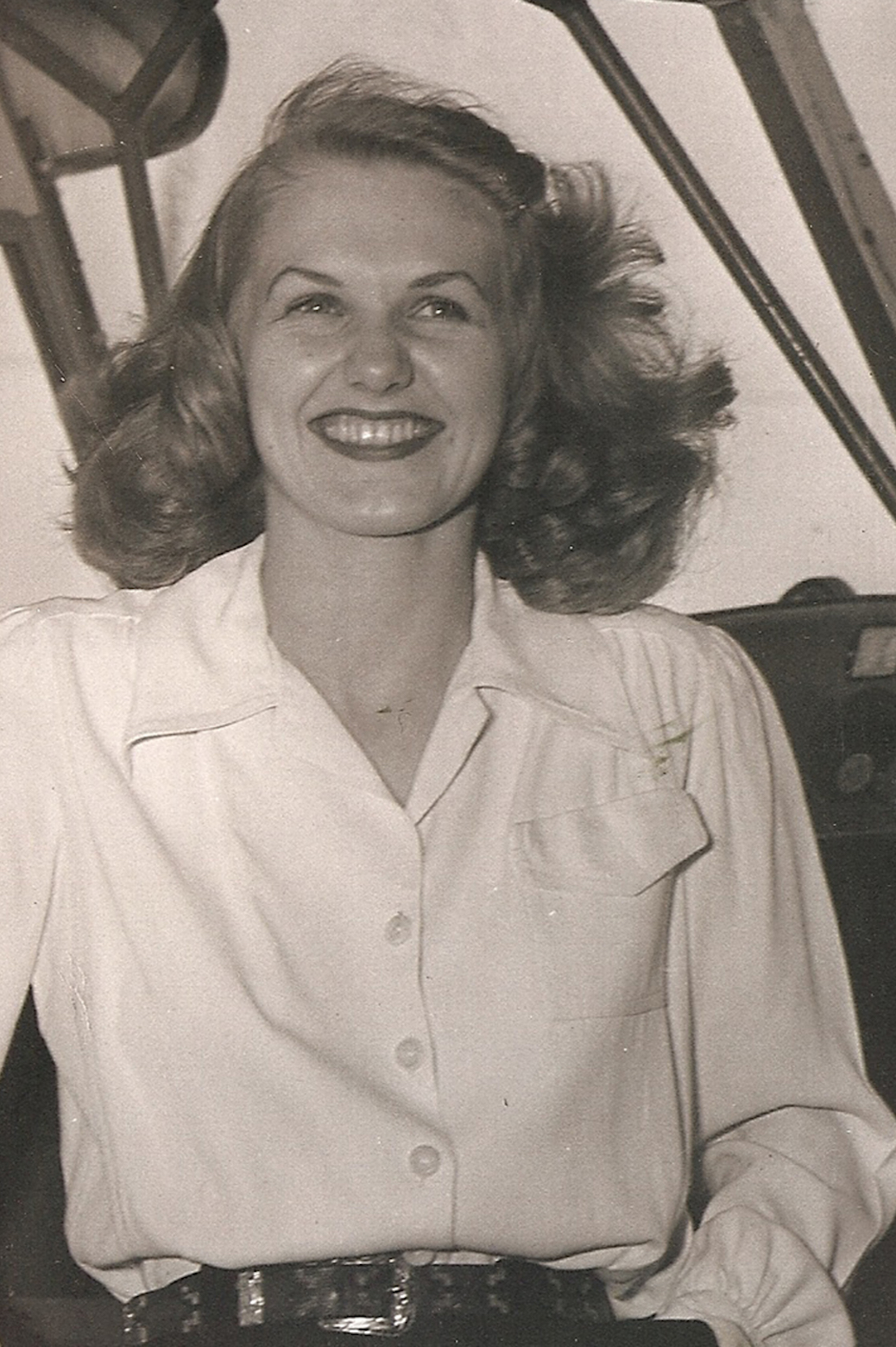

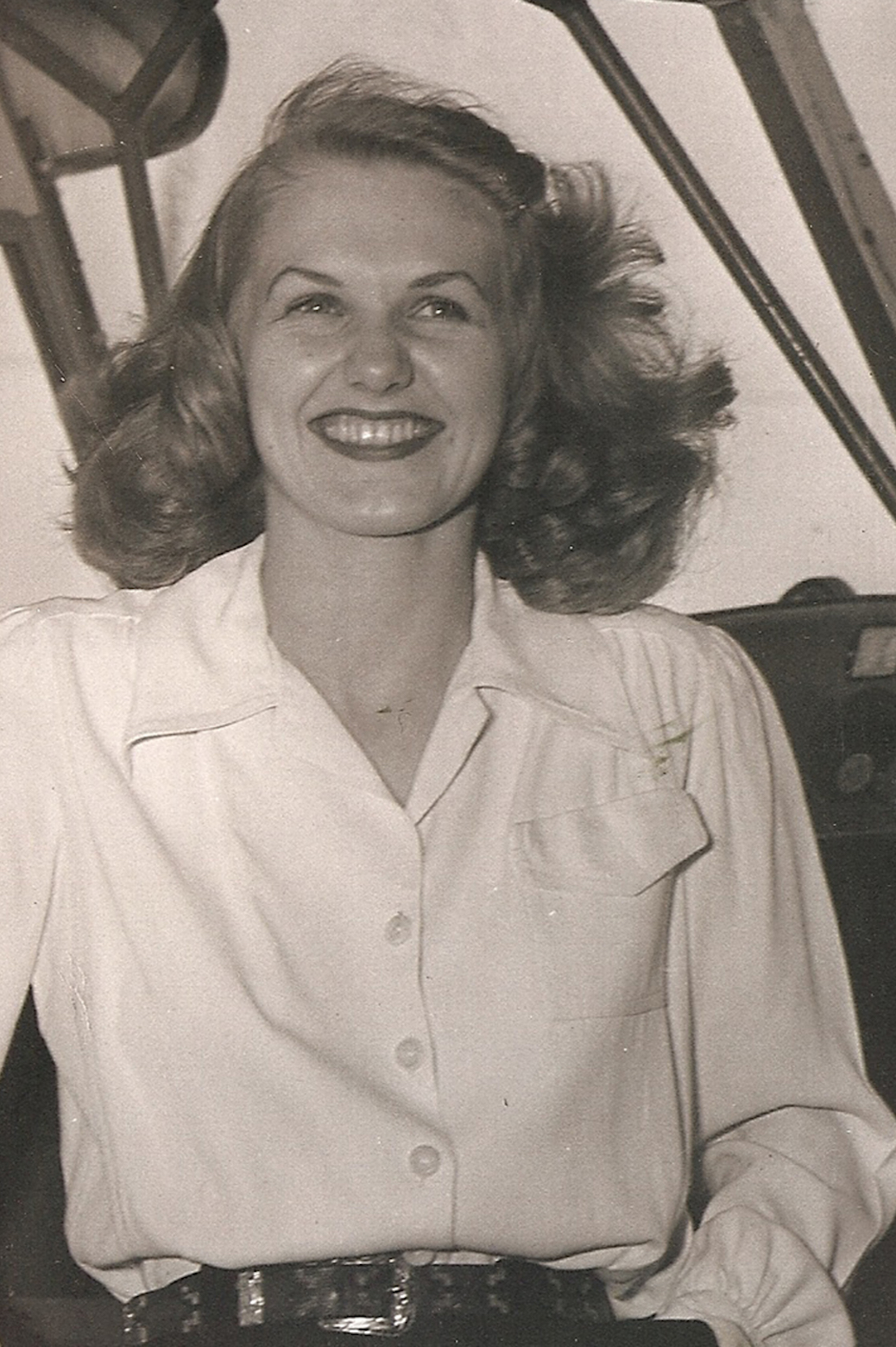

Elsie MacGill, the world’s first female aircraft designer, drew strength from the women who came before her.

Queen of the Hurricanes.

The name could be a fantasy novel – or a superhero moniker. It was a comic book. It’s also the truth.

Elsie MacGill (MSE Aero ‘29) is a Michigan trailblazer — the world’s first female aircraft designer. And at a time when jazz and flapper dresses pushed the Roaring ’20s boundaries of decorum, MacGill looked up at the walls barring her and those of her gender from rising in scientific fields, and she set about tearing them down from above.

The extraordinary life of the Hurricane Queen – from student to leader to activist – built upon the excellence of women who came before her. She dedicated the rest of her life to helping other women make the climb after her.

Enlarge

Enlarge

War Heroine

MacGill wasn’t deemed “Queen of the Hurricanes” based on temperament. Elsie earned the name when she led a highly demanding aircraft production line during the Second World War, overseeing a staff of 4,500 and streamlining operations as aeronautical factories rapidly expanded. Under her direction, it took only a year for Canadian Car and Company to produce the first Hawker Hurricane, bringing 35 year old MacGill into the heart of the WWI air effort as the aircraft’s designer and leader of production.

MacGill introduced de-icing controls and a system for fitting skis for snow landings – solutions that enabled the Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft to operate during the winter. These factories ultimately produced thousands of the Hawker Hurricane fighter aircraft for the British Royal Air Force. Elsie also designed and tested a new training aircraft – the Maple Leaf Trainer II. It may be the only plane ever to be completely designed by a woman.

While she never learned to fly herself, MacGill accompanied the pilots on all test flights – even the dangerous first flight – of every aircraft she worked on. Soon CanCar was building three or four planes every week and had become a wartime success story. MacGill was considered a war hero, representing Canada’s economic transformation during the war.

Enlarge

Enlarge

“War effort is a man staying and working an extra hour, or two or five hours a day,” said MacGill. “It is a woman cutting short her noon hour to get back to finish the job; it is someone taking home his problems to solve them after dinner; it is someone coming back in the evening to finish an assignment. War effort is something, which is as microscopic in the unit as the individual, but as mighty in the sum total as an army.”

MacGill’s efforts leading the production and making valuable adjustments to aircraft so that they could fly in cold weather made an impression well beyond the Royal Air Force – culturally iconic enough to inspire a comic book in her name, a 1942 series appropriately titled, Queen of the Hurricanes.

After the war the Queen worked in aeronautical consulting, and in 1946 MacGill became the first woman to serve as Technical Advisor for the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), where she helped to draft International Air Worthiness regulations for the design and production of commercial aircraft.

Following Family Footsteps

Consider the condition of women in the workforce, in higher education, and in the male-dominated field of engineering – countless other professions – in the early 1900s. The Canadian-born MacGill was a child when women earned the right to vote in her native country. Elsie was the first woman to graduate in electrical engineering from the University of Toronto in the 1920s.

While at school, MacGill was struck with polio. Doctors told her that she should expect to live the rest of her life in a wheelchair. Elsie forced herself to learn to walk again with two strong metal canes and earned a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering from the University of Michigan in 1929. Elsie was the first woman in North America, and likely the world, to be awarded a master’s degree in aeronautical engineering.

I think that with your training you are well placed to promote social goals, to open opportunities for everyone and to free people from the stultifying attitudes and practices that hamper their development. All of us, be we nine years old or fifty-five, have a stake in the future because we live in it. You who are young have the greatest stake for you have the longest time there: HOW WILL YOU USE YOUR EXTRA TIME?

— Elsie MacGill

Elsie MacGill broke new ground, just as her mother and grandmother had before her. Grandmother Helen MacGill was a journalist and a well-known women’s rights advocate throughout Canada. Elsie’s mother, Helen, was the only woman in her college class in 1889, the first female graduate of the University of Toronto, and the first woman in the British Empire to receive a degree in music. Helen Emma Gregory MacGill became Canada’s first female judge and, for many years, the country’s only female judge.

While recovering from breaking her leg in 1953, MacGill picked up a pen to write her mother’s biography. MacGill published My Mother, the Judge: A Biography of Judge Helen Gregory MacGill, in 1955. Delving into her mother’s philosophy, experience and idealism inspired Elsie to commit herself even more to women’s rights in the 1960s, advocating for abortion laws, fair wages and paid maternity leave.

Elsie MacGill was a creative leader and a talented engineer. She was passionate about designing aeronautical solutions for aircraft and presenting her leadership through writing. But most of all, she wanted to see the world grow in equity and equality.

“Perhaps because of my mother, I never forgot, throughout my long career, that many women in Canada do not have access to the opportunities I enjoyed. I have received many engineering awards, but I hope I will also be remembered as an advocate for the rights of women and children.”

There’s still work to do. For the past two decades, 20 percent of engineering school graduates are female but only 11 percent of practicing engineers. Michigan Engineering is among institutional leaders with an undergraduate class that over 25% female. But until all engineering graduates can soar, the Queen of Hurricanes has left behind a legacy and a question: what are you doing to bring others up?

Other Michigan Trailblazers

Enlarge

Enlarge

First female engineering graduate

Mary Hegeler, BSE Mining Eng 1882

In 1882, Mary Hegeler became the first woman to earn a bachelor of science degree in engineering from the U-M. Hegeler studied mining engineering as preparation for taking the reins of her father’s company, the Matthiessen-Hegeler Zinc Company in LaSalle, Illinois.

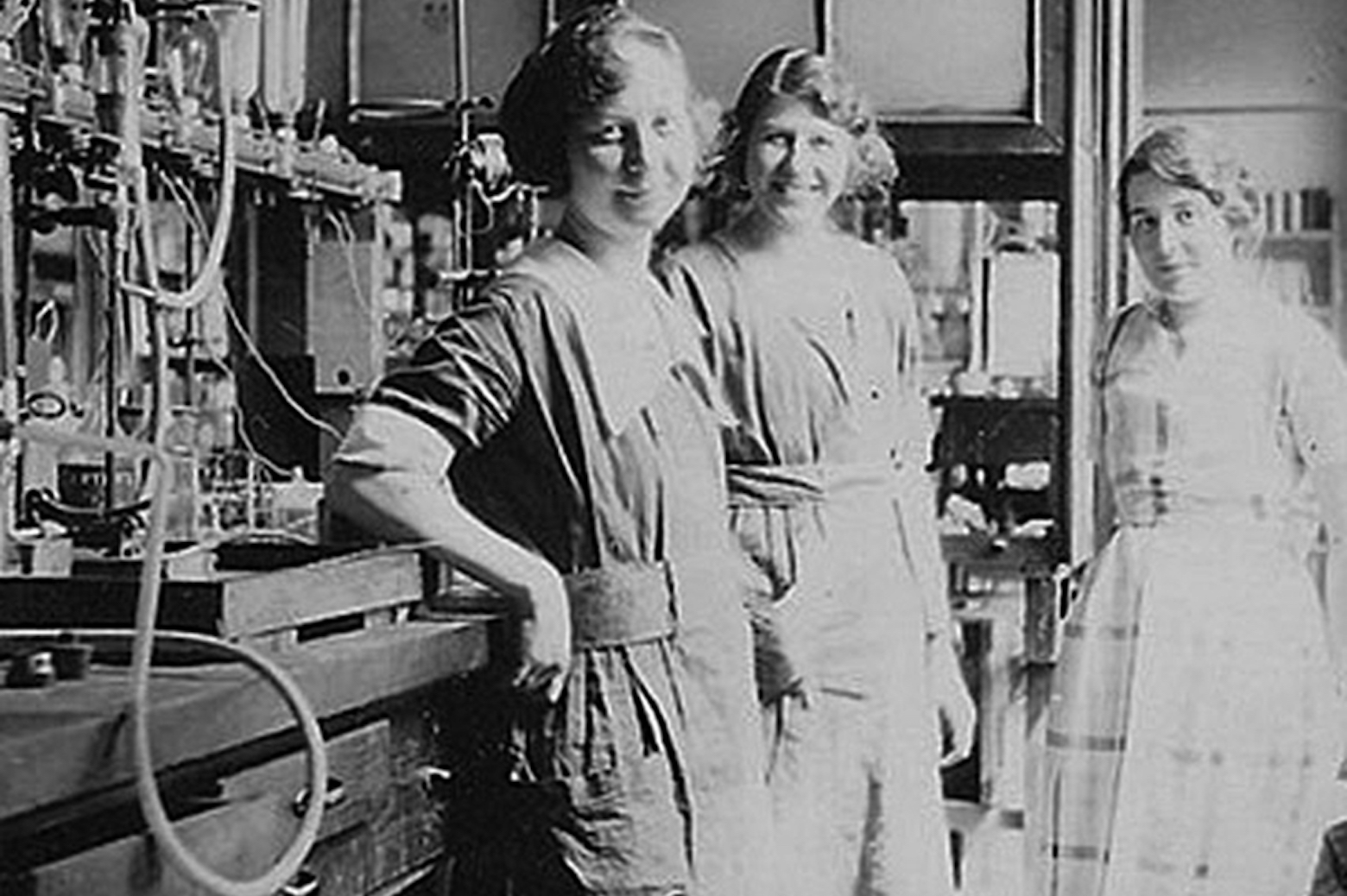

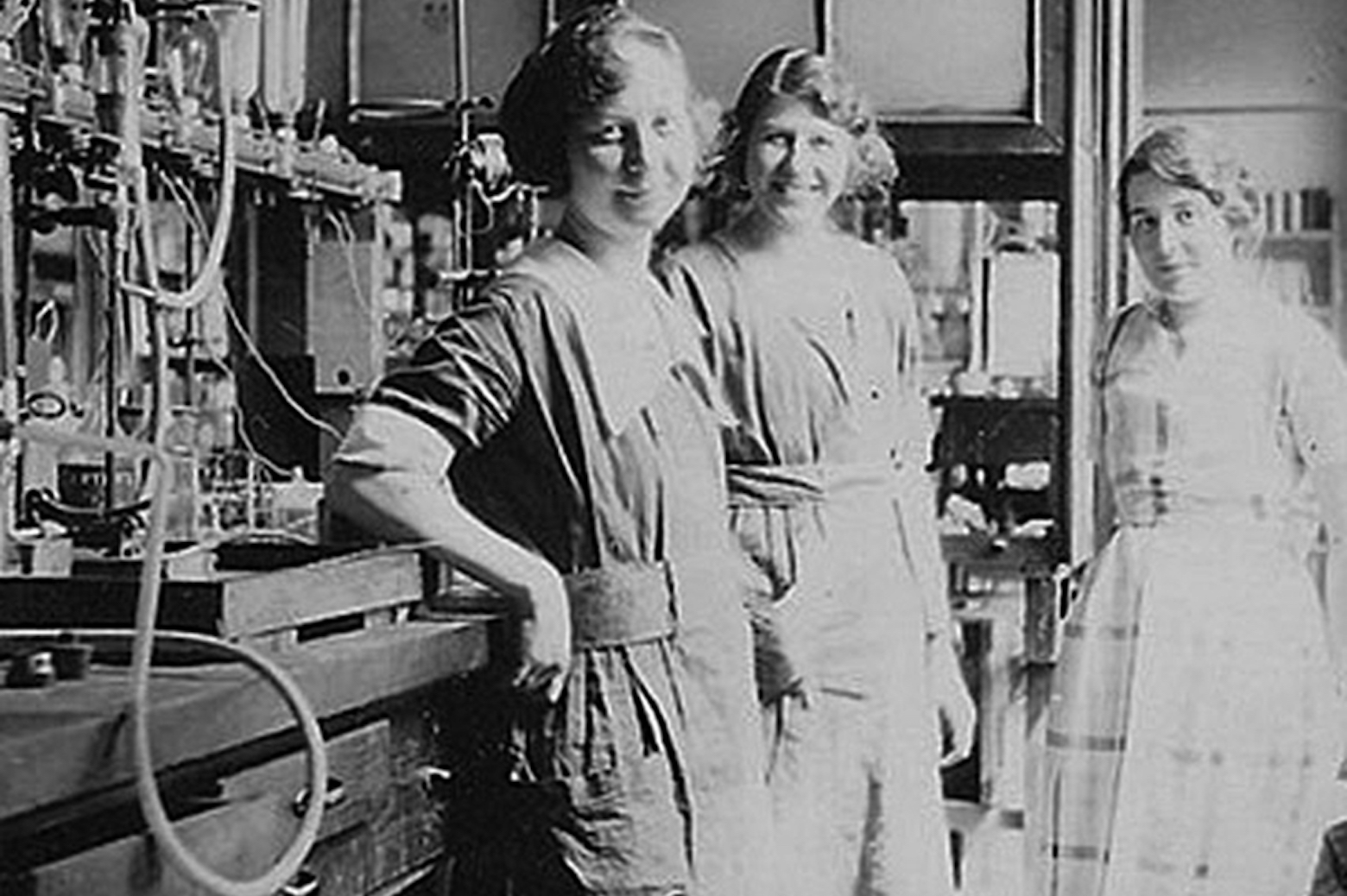

For advanced studies, Hegeler returned to her father’s native Germany, working in a laboratory under her cousin, Clemens Winkler at the Bergakademie Frieburg in 1885 and 1886. Though her presence was tolerated in a laboratory setting, Hegeler was required to be in a separate lab from the men (lest she distract them). Winkler is credited with discovering germanium while Hegeler was working at the Bergakademie, but it is unknown whether she played a role. Hegeler wasn’t allowed a degree, but she scored top marks in her courses.

When she returned to Matthiessen-Hegeler Zinc Company, Hegeler was involved in operations and was eventually appointed president by her father in 1903. After his death, the Matthiessens tried to oust her from leadership. Through a series of legal wranglings, however, she maintained her position and eventually bought out the Matthiessens in 1926.

While she was a formidable engineer and business woman, Hegeler also married Paul Carus and had seven children. Her grandchildren remember her as warm but reserved.

Engineering iconic architecture

Marian Sarah Parker, BSE CE 1895

Marian Sarah Parker graduated with a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering in 1895. Parker worked as a structural engineer and participated in constructing some of the most notable buildings in early 20th century New York City such as the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, the Broadway Exchange, and the Flat-Iron Building. Parker served her firm by designing the steel frameworks.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Blamed as an “absent mother”

Dorothy Brophy Hall, BSE ChE 1918

Dorothy Brophy Hall was a talented metallurgist for General Electric, successfully filing for several patents, and a fellow of the American Academy for the Advancement of Science. She also was Michigan’s first female chemical engineering graduate, earning her BSE in 1918.

But when faced with the loss of her firstborn child to meningitis, her family and society turned her achievements against her, as though the death could have been prevented if she had stayed at home according to social norms. Hall left her career and had two more children, but she never went back to research.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Fighting for her rights

Fay Ajzenberg-Selov BSE Eng Phys ’46

The daughter of Russian immigrants, Fay Ajzenberg-Selov had the iron will needed to break into a scientific academia almost completely ruled by men. She started out at U-M, earning her degree in engineering physics in 1946. During her post-doc at Caltech, Ajzenberg-Selov wrote the first of many major review papers on studies of light atomic nuclei, mostly those in the first two rows of the periodic table.

But the fight came when she applied to a tenured position in the physics department at the University of Pennsylvania. Her “inadequate” number of publications outstripped everyone in the department, save Nobel laureate J. Robert Schrieffer. When she filed complaints, the university was threatened with state and federal lawsuits if it didn’t hire her.

Ajzenberg-Selov’s skin would have been thick enough to bear it, but she said she didn’t face recriminations once she joined the department. Rather, they accepted her because she had won.

Enlarge

Enlarge

No girls in my engineering school

Sally Farquhar Shumway, BSE Eng Math ’47

“No, you don’t get it. I’m going to be the engineer.”

That’s what Sally Shumway (nee Farquhar) told her advisor when he recommended transferring to secretarial school. “You’re doing well. You’d make a great secretary for some engineer,” he said.

Compared to the open hostility she faced when she first enrolled, the condescension was an improvement.

“I don’t want any girls in my engineering school,” she recalls Assistant Dean Lovell saying.

But not only was Shumway’s resolve unwavering, so was her mother’s faith in her. “My daughter has a scholarship to your engineering school,” was the response. Shumway went on to earn her BSE in Engineering Math in 1947.

Out of school, she worked for Ford, then for the automotive parts company Fram, and finally with an engineering consulting firm out of Washington, DC. Like many of her generation, she stopped working when she had children. But her domestic life was upturned when her husband became mentally ill and died.

With four children, the youngest just two, Shumway returned to work, first at Fram again and then at Ford. By this time, the culture had shifted enough that she saw companies creating leadership positions specifically so that women could fill them. Equal opportunity window-dressing.

Suspicious of these roles, Shumway took only positions that previously had been held by a man, to be certain they were “real.” By the time she retired from Ford, she had worked there for 19 years.

Enlarge

Enlarge

India’s first female microwave engineer

Rajewari Chatterjee MSE EE ’48, PhD EE ’53

Rajeswari Chatterjee was deeply aware that few Indian women had the opportunities afforded to her. As she made the most of them, eventually becoming chair of the department of electrical communication engineering at the Indian Institute of Science, she remained committed to mentoring other young female engineers and speaking out against the caste system.

Chatterjee was fortunate to grow up in a broad-minded family that valued education for women as well as for men. Her grandmother had been a leader in the fight against child marriages and the practice of forcing widows into servitude, and would found a school after her own husband died.

After completing her bachelor’s degree in mathematics in 1942 and a master’s in physics in 1943 at Mysore University, Chatterjee worked as a research student at the Indian Institute of Science until 1947. Then, on a grant from the interim government during the transfer of power from Britain back to India, Chatterjee attended the University of Michigan to study electrical engineering.

The voyage took 30 days by sea, setting off from Singapore. Chatterjee earned a second Master’s, trained at the National Board of Standards for eight months, then returned to Michigan for a PhD in electrical engineering. She was now equipped to do her own pioneering work in microwaves and antennas.

Returning to India in 1953, Chatterjee took a position on the faculty of electrical communication engineering at the Indian Institute of Science. Over her career Chatterjee supervised 20 PhD students and published more than 100 research papers and seven books in microwave engineering and antennas. Honors include the Lord Mountbatten prize for best paper, Institute of Electrical and Radio Engineering and the J.C. Bose Memorial prize for best research paper from the Institution of Engineers.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Computing executive

Irma Wyman, BSE Eng Math ’49

“I grew up being told that I would never go to college, that I shouldn’t get my hopes up, that there would be no possibility of me doing that,” said Irma Wyman. But then she received a Regents Scholarship to the University of Michigan. As the only recipient from her high school, Wyman felt her good fortune was probably influenced by the effects of World War II.

“The number of guys in my high school graduating class was pretty thin – so they gave it to me,” said Wyman.

Several years later, the tables would turn. WWII veterans returning from overseas flocked to universities under the GI Bill. Wyman felt pressure to justify her presence as a women in the College of Engineering. It took strength and determination to overcome discrimination from faculty and students. Only two of the roughly seven women in her freshman class made it to graduation. Others either married or changed their majors.

“I felt that if I gave up, I would be rewarding all these people who said I couldn’t do it, I shouldn’t do it,” said Wyman. Her grades were good enough to qualify her for Tau Beta Pi, the engineering honor society, but it was not yet open to women.

When she graduated with a BSE in Engineering Math in 1949, Wyman couldn’t find an employer who would accept a female engineer. She continued the job she had as a student at the Willow Run Research Center, manually calculating the trajectories of missiles.

At a Navy research facility, Wyman discovered that a computer built by Harvard could automate these calculations, and she quickly learned to harness its power. Her talent caught the attention of the National Bureau of Standards (now the National Institute of Standards and Technology), which hired her to work on several different prototype computers around the country. By the mid 1950s, Wyman had experience with at least eight early computers.

“That was exceedingly rare at the time,” Wyman said of her experience. “At this point things were strictly experimental; there were no two computers alike. Even the one you thought you knew would be different tomorrow.”

Wyman’s skills led her to a startup in Boston, which was acquired by Honeywell, Inc. She was a seasoned manager, but she recognizes the role of Title IX legislation in helping her reach the upper echelons of the company as a vice president, then chief information officer. In her new role, Wyman sought to ensure opportunity for other women. She posed a question to the women’s council:

“Every man in this place knows that you have to achieve success in the incentive plan to be considered for vice president; I asked them, ‘how many of you women even know that there is an incentive plan? The answer was none.”

Wyman also established the Irma M. Wyman Scholarship at the University of Michigan’s Center for the Education of Women. The scholarship supports women in engineering, computer science, and related fields.

Enlarge

Enlarge

Starting as a secretary

Patricia Lewis Pilchard BSE Aero ’50

Patricia Lewis Pilchard first attempted to fly while she was still riding a tricycle – by attaching wings to it. In the middle of trying to hammer shingles onto her trike with a rock, she was struck by her discovery: “I realized that there was a lot more I needed to know before I could fly,” she said.

Pilchard worked to save money for flying lessons at 12, and finally took them at 16 by joining the Civil Air Patrol. Then, in 1950, she earned her bachelor’s degree in aerospace engineering. Working at North American Aviation, she first got her foot in the door by promising to do secretarial work. The men on staff started giving her engineering problems to solve, and as she proved her competence she eventually was recognized as a fully fledged engineer.

Pilchard left North American Aviation when her first child was born and she didn’t return to work until 1979, when she was employed by the Navy at Point Mugu, California. “They were particularly looking for women. I thought that was kind of a kick that they had changed so drastically in that twenty-five years,” she said.

Enlarge

Enlarge

The first female African-American PhD physicist

Willie Hobbs Moore BSE EE ’58, MSE EE ’61

Before Willie Hobbs Moore earned her PhD in physics from U-M in 1972, she had already earned a bachelor’s and master’s in electrical engineering in 1958 and 1961. In tandem with her PhD research, Moore worked as an engineer in Ann Arbor for firms such as KMS Industries and Datamax Corporation.

After completing her thesis, Moore continued working as a research scientist at U-M until 1977, studying the properties of proteins through spectroscopy, or the light emitted when molecules release energy. She published more than 30 papers during those years.

In 1977, she moved to Ford, where she expanded the use of Japanese engineering and manufacturing methods. Ebony magazine named Moore one of the “most promising black women in corporate America” in 1991.

Moore volunteered her time to help Ann Arbor youths and college students succeed in school, tutoring them in math and science. The first rule of survival, she is reported to have told them, is, “You’ve got to be excellent.”